Having written a few posts on Dorothy Campion and her book Take Not Our Mountain, I have always wanted to find out what happened to her and her family. Now photographer Dylan Arnold has published a book, in Welsh, with photo's

and stories of lost and forgotten places in Wales, including Nyth Bran, where Dorothy lived. Information on the

book and where to buy it can be found here and here

If you would like to find out more about Dylan's work please have a look at his website or his facebook page

Dylan has been very kind and sent me Dorothy's story (in English) and has given permission to publish it on my blog, for which I am very grateful. Here it is:

THE CAMPIONS

It’s

unclear when Hugh Tetlow’s Aunt Nancy, and her mother left Nyth Bran,

but in 1947 a new owner had

taken it on. Thomas Whawell Campion, or ’Whay’ as he was known to all,

was an ex-commando. He had been medically discharged from the army in

1946. At the end of the war, Whay had a haemorrhage on his lung as a

result of contracting tuberculosis. At the time,

effective medicines had not yet been developed for TB, it was therefore

regarded as a serious, contagious illness. Due to the severity of

Whay’s condition, he had not been given long to live. He’d allegedly

contracted TB whilst hunkered down in a cave in Greece,

fighting alongside Tito’s partisans. He regularly suffered recurring,

debilitating bouts, which would leave him bed-bound for a week or more.

Whay eventually overcame it, but it took several years before his

condition drastically improved, against all odds.

When the war ended in Europe, Whay returned to the family home in Betws

y Coed. He could have stayed at home to be nursed by his doting mother

and his two older sisters, but Whay could never have been a dependent

invalid. He decided that he needed a home of

his own; preferably an isolated and quiet bolthole, where he could

recuperate from his illness, lead a simple, peaceful life, and escape

the horrors of war that haunted him.

The

remote cabin of Nyth Bran was perched over 800ft at the end of a rough,

unmade mountain track above

Capel Curig. It had come up for sale, and ticked all the boxes for

Whay. There were wild acres of woodland and moors surrounding the house,

not to mention the spectacular views over the valley below, and towards

Moel Siabod to the South. When Whay bought Nyth

Bran, it was in a state of considerable disrepair. He undertook the

extensive renovations himself over several months. He rented three

hundred acres of the surrounding mountain land for his new flock of one

hundred and thirty sheep. Whay cladded Nyth Bran’s

lounge in half cut sections of logs. He had worked as a timber

contractor for the coal board supplying pit props, which is where he

‘sourced’ the lengths of wood. He decked the hallway with wooden

planks that were once the floorboards of The Royal Oak Hotel

in Betws y Coed. “Whay was able to turn his hand to anything, and often

did, in order to make ends meet. Everything at Nyth Bran, he did

himself. He’d build sheds from scratch and repair everything. He’d

completed an automobile technician course in the army

for a couple of months. He’d take an engine out of the jeep and fix it.

Nothing fazed him at all. He seemed to be able to do anything with a

screwdriver and a hammer.”

Whay

could easily live off the land. He was fearless and self sufficient. He

was a resilient, determined,

and resourceful character, with more than his fair share of charm,

humour and charisma. Born on the 27th of June, 1918, he could not walk

until he was seven years old, following a childhood accident that had

left his legs crushed. By the age of fourteen, he

was working on deep-sea fishing trawlers in the North Sea during his

school holidays. Whay overcame his physical challenges and pursued his

great love for the outdoors. Rock climbing was a particular passion of

his. As well as being a formidable climber, he

was a qualified, expert skier and a well respected mountain guide in

Snowdonia and the Austrian Tyrol. He was also an active member of The

Mountain Rescue in Snowdonia. Before the Second World War, Whay embarked

on a mountaineering and research expedition

to the far north of Norway, conquering a previously unclimbed peak on

the Sweden/Finland border, while collecting data on plant and animal

life. Whay also sailed on two expeditions as a scientific researcher,

collecting geographical data and plant specimens

from South America and Newfoundland for The British Museum. He also

embarked on a museum funded Arctic expedition. He then set sail around

the world on a small yacht for two years, for his own pleasure.

It

was his spirit of adventure that lead him to join the army in 1939. He

was sent with the British Expeditionary

Force in 1940 and later evacuated to Dunkirk with his unit, The

Sherwood Foresters. Whay rarely spoke about the war with his family, but

later said that Dunkirk had been ‘horrific’. He had been wounded in

battle several times and bore many physical and emotional

scars to prove it. Whay escaped death numerous times on the

battlefield, once by bending his head to light a cigarette whilst a

bullet which would have severed it whistled past. After Dunkirk, Whay

signed up with No.2 Special Services Brigade, which would

later develop into the formation of No.9 Commando. Later he would also

serve with No.11 Commando. Whay was in at the start of the Commandos,

when they were formed in 1940, on the order of Prime Minister Winston

Churchill. It was decided that an elite force

was needed that could carry out raids against German-occupied Europe.

These soldiers were hand picked for their intelligence, capability

and resilience. Their training was nothing short of revolutionary at the

time, and much of it is still used today.

Whay

spent most of the next six years of his life serving in various

European countries

during the Second World War, for which he was awarded the Military

Medal, amongst others. He fought in Sicily, Crete, France, Italy and

Greece, and was also sent out twice to the Middle East. Whay fought in

several infamous wartime battles, and played a part

in the daring raid on St.Nazaire, France in 1942, and the brutal Battle

of Anzio, Italy in 1944.

When

Whay returned from the war, it had taken it’s toll on him and

inevitably changed his outlook on life.

Nyth Bran gave him the much needed solace he needed to recover from

tuberculosis, and the grim wartime ordeals he had experienced. His two

dogs, Hemp and Trigger, were his sole companions at lonely Nyth Bran.

Despite the solitude he’d craved for after fighting

in the war, there were times he felt very isolated. That was about to

change in 1952 when he met Dorothy Johns. Dorothy was born into a

wealthy, high-society upbringing in Manchester, and consequently, had a

taste for the finer things in life. The only passing

acquaintance she’d had with Snowdonia was when she had raced through in

her father’s Bentley during motor car trials. She liked socialising,

theatres, expensive clothes and dining at fine restaurants. Dorothy had

tried her hand at a few things, including

modeling, horse-show jumping, and for a brief time she was a racing car

driver. According to Dorothy, she was happiest when she undertook her

training for the role of auxiliary nurse. Dorothy had a young daughter,

Jane, from a previous ‘disastrous’ marriage,

who was three years old when her mother met Whay. Dorothy’s father had

been a successful businessman for many years until his company went

bankrupt. Following the liquidation, the family moved to Rhos on Sea,

North Wales, to start a new life, but sadly Dorothy’s

father died of cancer not long afterwards. Dorothy and Whay seemed an

unlikely couple but nonetheless they fell very much in love. Whay hadn’t

had much experience of being around children, but after a tentative

start, Whay and Jane warmed to each other. After

Dorothy and Jane had stayed at Nyth Bran a few times, Whay decided he

couldn’t live there alone without them anymore. After a brief courtship

lasting a few weeks, Whay and Dorothy were married in Betws y Coed on

Christmas Eve 1952. Dorothy’s mother doubted

her daughter’s suitability to a rural life.

Dorothy

and Jane settled into life at Nyth Bran. At first, Dorothy found it a

jarring culture shock from

the affluent city life she’d left behind. Facilities at the farm were

basic. There was still no electricity, and water had to be pulled from

the well. Later on, when Whay had connected the taps to the water

supply, bathing during Springtime would often result

in a bath full of frogspawn. Dorothy, however, was determined to prove

her capability and devotion to Whay. She took on duties as wife,

homemaker and shepherdess. Whay farmed, and made ends meet by taking on

additional work as a local mountain guide and working

for the Forestry Commission. Jane thrived at Nyth Bran, she and Whay

became inseparable. In Jane’s own words, she was “like his shadow”. She

would look forward to getting up early to help Whay with the sheep,

feeding the hens, fencing and whatever other duties

had to be done on the farm. It was only a quick walk down Nyth Bran’s

track to reach the primary school, where Jane made many happy memories.

Dorothy wasn’t so keen on her daughter learning Welsh though, and later

sent her to an English medium boarding school

in Llanrwst.

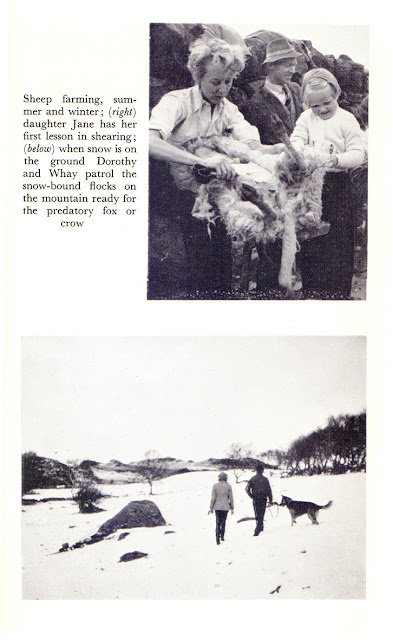

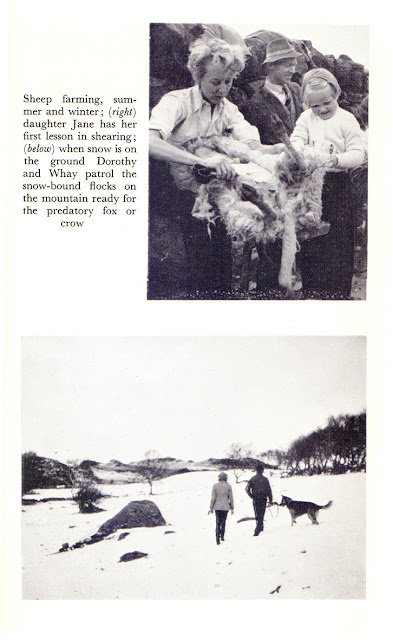

During

the snow and blizzards of the winter months, Whay would ski around the

mountainside on his daily

rounds to check the flock and dig the occasional sheep out of heavy

drifts. He would pull a thrilled Jane along in a sled he’d made for her

from some of his old skis. They were accompanied by Dorothy and their

dogs, Carlo, Hemp, Trigger and Bobby, who helped

to sniff out any snow-buried sheep. There was a particularly big freeze

the year Whay moved into Nyth Bran. The farm was engulfed in snowdrifts

to the point that Whay had to lift the skylight in the kitchen, exit

the building via the hatch and skied to Betws

y Coed to get food using some old Norwegian cross country skis he had.

In

the spring, Nyth Bran welcomed its newborn lambs. The kitchen would

echo to the bleats of the orphaned

ones. Dorothy and Jane would feed these lambs and keep them warm by the

Aga. One year they looked after abandoned triplets, which they named

Buttons, Bows and Loppy. Buttons and Bows were duly named because that

was the song that happened to be playing on

the radio when Whay bought the lambs in. Loppy earned his moniker

because his ears never stood up. Whay was never a farmer in the

traditional sense, he just did what he had to do in order to survive and

provide for his family. There wasn’t enough money to

be made farming Nyth Bran’s three hundred acres alone, and despite Whay

taking on additional work whenever and wherever he could, money was

always tight.

Whay

sometimes had to carry out tasks he disliked, such as destroying lambs

that had been born deformed.

One day Jane saw that Whay was going to shoot a pair of lambs that had

been born with deformed legs. Dorothy explained why, showing Jane their

twisted legs, and reasoning with her that it would be cruel to let them

live in pain and unable to walk properly.

Jane asked “If Daddy shoots them, will they go to heaven with grandpa?”

A

week later a Land Rover roared up Nyth Bran’s track. To Whay’s delight

and surprise, it was an old army

friend of his. The ex-soldier had a wooden leg, which Jane had observed

and remarked “Daddy, look at his crippled leg. Do we have to shoot him

too?”

Dorothy’s

mother would occasionally visit Nyth Bran from her home in Llandudno.

For a while she lived at

Bryn Brethynau, the cottage just below Nyth Bran. Along with

neighbouring Waen Hir and Tyn y Coed, it was originally one of the farms

that each had a hundred acres, that made up the three hundred acres

that Whay rented. Dorothy’s brother, Peter, moved in to

Nyth Bran for a while when he was around thirteen. He loved helping out

on the farm and remembered those days fondly. Peter went to school at

Capel Curig, and after finishing agricultural college at Glynllifon, he

worked alongside Whay timber contracting in

the forestry for about ten years. He looked up to Whay and later

recalled “Whay was like a father to me, a lot of people thought we were

father and son”.

Whay

and Dorothy had discussed the issue of children. They both wanted Jane

to have a sibling. It was also

their hope that one day, a son and heir would be born to them, so that

he may continue shepherding at Nyth Bran and develop on the foundations

that Whay and Dorothy had laid. During one, hot summer afternoon, the

pair were felling a half-windblown oak tree

near the house using a two handled saw. They were chatting away happily

when the tree gave a sharp, warning ‘crack’. The tree swayed and

teetered. “Jump!” shouted Whay, but it was too late. Dorothy was flung

to the ground, unconscious, with the oak tree across

her back. She regained consciousness in Bangor Hospital. Luckily, no

bones were broken but surgery had to be performed on her abdominal

wounds. Dorothy’s stomach muscles were badly torn and her left fallopian

tube and ovary were removed. The right fallopian

tube remained but was critically damaged and unlikely to function

again. The doctors broke the news that it was very improbable that

Dorothy would be able to give birth again. It was a devastating blow for

the couple. Whay was heartbroken and blamed himself

for Dorothy’s injuries. Dorothy had difficulty accepting the medical

prognosis and insisted on going for further tests over the following

months, hoping that somehow she would recuperate and improve to the

point that pregnancy could be a possibility again.

The grim situation hung over the couple like a dark cloud and Dorothy

retreated into herself. Whay supported her but was also grief stricken

himself. He eventually suggested to Dorothy that she should stop going

for the medical tests and accept the situation,

as all the tests served to do was prolong their agony.

The

strain of the situation weighed heavily on the couple. Dorothy

suggested some time later that they

could adopt a boy to bring up as their own. Whay immediately agreed to

the idea. Dorothy knew of an orphanage with an adoption agency in

Manchester, so later that night, they wrote their application.

The

daily trips down Nyth Bran’s track to collect the mail in the morning

were suddenly filled with much

anticipation for the eagerly awaited response from the adoption agency.

It was two weeks later when Whay ran into the house, waving a letter

and grinning from ear to ear. A child would be placed with them for

adoption as soon as possible, providing that all

necessary reports and references proved satisfactory. The couple were

over the moon and danced around the kitchen. Dorothy set about gathering

blue baby clothes and woollies. Together they prepared one of the

bedrooms as a nursery, which they painted pale

blue, in readiness for the future shepherd of Nyth Bran.

The

adoption agency let Whay and Dorothy know that a baby boy would be

waiting for them in Manchester on

May 21st; they were over the moon. The Campions lived a fairly isolated

life at Nyth Bran, and since sending the application to the adoption

agency, Dorothy had kept herself to herself and stayed at home all the

time. The reason for this was because she had

decided that only their immediate family, doctor and solicitor should

know that the baby was adopted. Dorothy wrote “If the time should come

when the child must learn that he was adopted, he should hear the truth

only from our own lips”. So in preparation

for their son’s arrival, Dorothy assumed the pretence of being an

expectant mother near her time. A Capel Curig resident remembered seeing

her around the village at that time with a pillow under her dress. They

couldn’t fathom why she was pretending to be

pregnant, but unbeknownst to Dorothy, it seemed that her ruse had

failed to convince the locals.

The

day finally arrived when Whay and Dorothy were to meet their new son.

They excitedly drove the four

hours to Manchester full of hope and anticipation. The baby was

beautiful. He had bright, blue eyes and a mop of golden hair. They had

called him Robert Whaywell Campion. Whay and Dorothy were ecstatic and

couldn’t wait to bring him home. For the first time

in months their lives felt complete.

It

was shortly after Robert’s arrival at the farm, that the electricity

board finally connected Nyth Bran

to the grid, despite the rest of Capel Curig being connected some time

ago. There was much excitement when Robert was fed and bathed by

electric light! Just as Jane had accompanied her parents around the farm

as soon as she’d arrived there, so too did Robert,

as the family carried out their daily duties. They carted him

everywhere in his blue cot and laid him in shaded areas as they got on

with their work. Jane absolutely doted on her new baby brother, and was

always on hand to keep him amused and comforted. Whay

couldn’t have been happier. He was very attentive father to Robert,

nursing and feeding him gently. Whay loved pushing Robert in his pram,

talking animatedly to him all the while. Since Robert’s arrival, Dorothy

and Whay felt closer and happier together than

they had done in a long time.

One

morning at Nyth Bran, Dorothy alleged that an unexpected and sinister

phone call took place between

her and an anonymous woman. The call was to turn their lives upside

down. According to Dorothy, the caller first asked how Whay’s lung was

currently doing. Assuming that the woman was a friend of Whay’s, Dorothy

replied that it was fine and that Whay had never

felt better. The caller then asked when Whay had received his last

check-up and xray, to which Dorothy replied that it was six months

previously and all was satisfactory. Dorothy, sensing an unpleasant tone

to the caller’s voice, asked who she was, but the

woman gave nothing away. The caller then suggested that Robert had not

been born to Dorothy and Whay, stating that Somerset House had no record

of a baby being born to them. The caller then informed Dorothy that she

would be writing to the Health Centre to

share information that they ought to know, like the true state of

Whay’s health, and that in the caller’s opinion Whay wasn’t a fit person

to be taking on the responsibility of an adopted child. The caller then

hung up. According to Dorothy, she immediately

called the telephone exchange to trace the caller, but the operator

could only confirm that it had been a local call.

Whay

had never made a secret of the fact he’d had TB years ago, or how

seriously ill he had been as a result.

The Campions neglected to include this information on the adoption

form, since Whay had recovered to perfect health. The Campions contacted

their solicitor, who advised they do nothing and wait, in case the call

was a bluff. Two days and nights passed, during

which their lives felt in limbo. There was only a matter of days to go

when Robert’s adoption papers should have been signed and completed and

The Campions’ probation period with Robert were to come to an end. On

the next day, the Health Officer telephoned.

The Welfare Centre had received an anonymous letter giving all the

details of Whay’s past illness, stating that he had a haemorrhage in

1946, that there have been a cavity in one lung, that after the war it

had taken him six years to recover his health, but

he still went to Llandudno hospital for a twice yearly checkup, and

that in the opinion of the writer he was not a fit person to father an

adopted child. Despite Whay’s perfect present health, the health officer

was perturbed. If the facts in the anonymous

letter were true, the officer stated that the Campions case must be

reconsidered. Whay and Dorothy begged and pleaded how much Robert meant

to them. They frantically wrote to the orphanage Robert had come from,

to Whay’s doctors, three solicitors and a barrister,

and their local Member of Parliament. Despite their best efforts, the

Health Officer telephoned her final word on the adoption society’s

behalf: Robert must be returned to the orphanage.

It was

1955, Robert had been at Nyth Bran for three or four months at this

point. Whay and Dorothy had

never regarded him as adopted, but as their very own; ‘a gift from

God’. When they drove to Manchester to hand Robert back, they were both

utterly broken. In the weeks that followed, they were unable to eat,

sleep or even think straight. They saw visions of

Robert everywhere at home. The farm was neglected while they grieved.

Their sense of pain and loss was unbearable. Dorothy described feeling

like “the only occupants of a deserted ship, drifting without a compass

or even a star to guide it”.

Spring

came to the farm, and with it, the realisation that the family would

either have to sink or swim.

It was lambing time and there was much work to get stuck into if they

were to survive. Whay and Dorothy broke the news to the villagers about

what had happened to Robert and tried their best to get on with their

lives. They eventually managed to regain some

of their vigour to get on with their daily duties.

As

previously mentioned, there was never much money to go around, but

having neglected the farm for so

long after losing Robert, the Campions were feeling hard financial

pressure. After coming to live at Nyth Bran, Dorothy had taken up

writing to fill in the hours that she was on her own while Whay was out

working. Dorothy had penned a semi autobiographical

manuscript over the last few months which was about to save them

financially for the time being. Luckily for the Campions, Dorothy had

her first book published that year. ‘1000ft Up’ was a collection of

mostly fictitious stories, loosely based on elements

of Dorothy’s life. The book didn’t achieve any significant critical

success but it did sell reasonably well, and earned her some much needed

funds.

Dorothy’s

sister, June Johns, was also a writer. She worked as a journalist for

The Daily Mirror. June

pulled a few strings with her media connections, so that in May 1956

‘Woman’ magazine published Dorothy’s autobiographical account of her

life at Nyth Bran. The story was serialised and ran for several weeks in

the magazine. This bought Dorothy exposure, not

to mention some fame and fortune, which paved the way for the release

of her second book, ‘Take Not Our Mountain’ the following year. The book

told the story of The Campions’ lives as shepherds on their remote,

Welsh mountain farm. Her story captured the hearts

of readers across the nation and beyond. The book flew off the shelves

and was a huge success. The Campions started getting lots

of curious visitors coming up to Nyth Bran. Hundreds of readers of Take

Not Our Mountain, wanted to meet Dorothy and her family

in person! Many of them got their cars stuck on the rough, steep track

along the way up to the farm. Whilst Take Not Our Mountain is

entertaining and mostly factual, there are aspects of the book that have

been romanticised or glossed over. Some recorded events

were possibly set-pieces for the purposes of storytelling. The main

difference between Dorothy’s written account and that of actual events,

is how Dorothy portrayed herself in the book. According to the book,

Dorothy worked alongside Whay on the farm, and

had immersed herself in all the different aspects of its daily running.

By all accounts, Dorothy did very little on the farm, and didn’t like

to get her hands dirty. Dorothy’s relationship with Jane was also not as

harmonious as portrayed in the book. According

to Jane, there was never much love or affection shown to her by her

mother, and that it was Whay who mostly took care and supported her.

Nevertheless, Take Not Our Mountain sold very well, earning Dorothy a

lot of money. She was asked to present talks to various

local and national groups, radio and magazine interviews and book tours

to promote the book. She would sometimes spend weeks away from home

during these promotions. During the course of the book tours and various

public and social engagements, she began to

mix with well-known authors and high profile people. Dorothy started

dressing in expensive clothes again. She had found moderate, new-found

wealth, not to mention some fame. She began to rekindle the life that

she had once been accustomed to, the life she’d

left behind when she married Whay.

At

this point, when Jane was about thirteen, she barely spent any time at

home.

During the week she was boarding at St.Gerards School in Bangor.

Dorothy had sent her there against Whay’s wishes. On weekends, Jane

would stay at her grandmother’s in Llandudno as her mother had demanded.

This may have been because things were getting fraught

between Dorothy and Whay at home. Jane continued at St.Gerards until

she completed her O levels, age fifteen. In 1959 Dorothy released her

third and final book, ‘The Perfect Team’. The book explored the teamwork

of police dog handlers and their Alsatian canine

partners. In the course of researching the book and gathering material,

Dorothy interviewed hundreds of police and armed services dog handlers

all over the UK. She traveled thousands of miles over ten months,

accompanied by her Alsatian, ‘Smokey’. He had been

the sire that she bred other dogs with. Liverpool, Manchester and

Birkenhead police forces all had dogs trained by Dorothy. She had been

commissioned by her publisher to write a fourth book about police

horses, which was to be called ‘Law in the Saddle’, but

that never materialized.

Dorothy

spent months on the road promoting ‘The Perfect Team’ across the UK.

She lived in various cities

during that time, mixing in high-society, literary circles again.

Jane’s suspicions that things weren’t well between her parents were

confirmed when a solicitor visited her at St.Gerards, wanting Jane to

speak about her mother in a divorce court. Later, at

the hearing, Jane told the court that she didn’t want to be with her

mother because she had never been the subject of her love or affection.

She expressed how it was Whay who had always cared for her, and who was

always there for her. Jane pleaded with the

courts to let her stay with her dad. It was at this point that

Dorothy called out “He’s not your dad!” That was how Jane found out that

Whay wasn’t her biological father. Jane was on her knees, sobbing and

hanging on to Whay, while he broke down too. In those

days, the courts almost always gave custody to the mother; this case

was no exception, despite Jane’s desperate pleas.

After

the divorce, Dorothy forbade Jane to get in touch with Whay again. Jane

desperately wanted to though,

and asked her grandmother’s advice about it one day. Her grandmother

advised against contact, knowing what Dorothy’s temper was like. As the

years passed, Jane never did get to speak to Whay again, but to this

day, he’s often in her thoughts.

Dorothy went

to live with her mother in Llandudno for a while, before eventually

moving to Sussex. After

finishing her O levels at St.Gerards, Jane followed her mother down to

the south of England, where she was enrolled at a finishing school at

Guildford. That was around the time when Jane met her mother’s new

partner, Dennis Luckham. Dennis was a wealthy businessman

who owned a large company making hospital equipment in Burgess Hill.

When Jane came home from school one weekend, Dorothy announced that

she’d married Dennis. They were wed on the 21st December, 1964. The

marriage had it’s fair share of problems before ending

in divorce in 1970. When they divorced, Dennis bought Dorothy a pretty,

thatched cottage in Huntingdon, where she lived till the end of her

days. Dorothy lived a lonely life there. She eventually met some

spiritual couples and joined them in following God. Dorothy didn’t

write any more books, but she kept herself busy writing poetry. Dorothy

died alone, aged fifty five, on 8th January, 1980.

After

Jane finished her schooling at Guildford, she went on to do nurse

training and worked as a nurse

for many years. She settled in Hastings, where she met her first

husband and had six children. Jane remarried in 1984 but sadly her

husband died of a heart attack 18 months later. She remarried again in

1987. Jane and her third husband had twenty years together

before he passed away in 2007. Jane currently lives with her son in

Kent.

Dorothy’s brother, Peter,

lost touch with Whay after the divorce. Peter moved to Llanrwst, where

he met his second wife. They emigrated to Canada in 1981 and have lived

there since. Peter farmed a ranch for a while, then took on factory work

for twenty five years before retiring in

2001. Peter and his wife have a son, daughter and grandchildren, who

live close by.

Whay

and Dorothy had a very acrimonious divorce. Whay carried on at Nyth

Bran but had given up farming

it by then. He worked most of the time for the Forestry Commission but

also took on various jobs to make ends meet, such as contracting,

general maintenance and small building jobs. He also drove a minibus for

The Swallow Falls Hotel. At some point around

the early to mid sixties, Whay met and fell in love with Olga Gross

(nee Parry). The pair were married in 1971. Olga was twice divorced and

had two sons, Andy and Michael. Andy was the youngest and was about

twelve years old when he moved into Nyth Bran, Michael

was eleven years older. Whay and young Andy were particularly close,

Whay treated Andy as his own son. Andy looked up to Whay and regarded

him as his dad. Olga and Whay did everything together, they were very

well suited and very much in love. Andy loved his

time at Nyth Bran, remembering the location as an ‘idyllic’ place to

grow up. “You could wander for miles and do what you liked. Although my

friends in Betws y Coed were only five miles away, they might as well

have been on the other side of the world”. Whay

had a couple of pet alsatians and Olga had a sheepdog and a couple of

donkeys. The donkeys were like big dogs that would follow Whay and Olga

everywhere on the farm. Whenever anyone would lay on the grass, the

donkeys would join and lie down too. Sometimes

they would even go into the house.

Although Whay was

tight-lipped about his military past, he would occasionally tell Andy

and Michael tales from

his commando days. Andy remembered Whay telling him about the time he

did his first parachute drop, and that it was going to be operational.

Whay had said that basically, he learned how to jump out of an aeroplane

-

by jumping out of an aeroplane. Another story involved him being

posted to Sicily. Whay was being chased at night by a German patrol. He

came to a wall, jumped over it and landed on a dead German soldier on

the other side. The corpse was bloated and

filled with gas. When Whay’s feet landed on the body it emitted a long,

loud fart. “Of all the things I had to land on, it was a dead German!

Lucky he was dead because there were live ones running up behind,

shooting at me!”

Andy

recalled Whay having a Certificate of Service on the wall at Nyth

Bran that listed all the countries

No.9 and No.11 Commando had served. Whay had an ‘X’ against most of

them, along with a copy of his medal awards at the bottom.

Unsurprisingly, Whay never spoke about how he had been awarded his

medals. It caused much consternation for him to talk about it.

Once, when questioned about them by Dorothy, he reluctantly and angrily

answered “They are pieces of silver, awarded for bravery, given to me

for the fine way I killed…” The Commandos did a lot of things that

these days would be regarded as unacceptable in

the modern world. Since the war, Whay had suffered with what would

nowadays be almost certainly recognised as PTSD (post traumatic stress

disorder). At night, he would sometimes wake the house up, screaming in

bed, plagued by terrible nightmares from the things

he’d seen during the war. Jane also recollected him suffering

nightmares when she lived there. Olga eventually persuaded Whay to see a

doctor about them.

In

1970 Andy left Nyth Bran to start an apprenticeship with the RAF. He

was eventually posted to Germany

but regularly came home on leave. A few years later came the

devastating news of Olga’s cancer diagnosis. Whay nursed her tenderly

throughout her illness and the pair spent all their available time

together. Whay would only work when they really needed money,

in order to maximise the time he had left with his wife. When Olga

became more immobile due to her failing health, she and Whay would mess

about on ‘monkey bikes’ around the farm for entertainment, as she could

not easily leave home at that point.

Olga passed

away in June 1976, aged fifty three. Whay was devastated. Andy returned

from Germany for his

mother’s funeral. Olga’s ashes were scattered on the mound outside the

back of Nyth Bran. When Andy was due to return to Germany, Whay said his

farewells and told Andy he’d see him at Christmas. Sadly, that would be

the last time Andy saw him. Whay sadly died,

broken hearted at Nyth Bran four months later, on October 17th, 1976,

aged fifty eight.

Nyth

Bran then passed on to Andy. He was only twenty one years old, and

still coming to terms with his

mother’s death when Whay’s sudden passing sent him reeling. It was

understandably a very traumatic time for Andy, who didn’t know what to

do with the house. Andy helped his friend out by letting him stay at

Nyth Bran for a year, in exchange for keeping the

house secure and in order.

The

last time Andy visited Nyth Bran was in 1978, to sort out his parents

belongings. He was

living in barracks in Germany and had little room to take anything back

with him. Consequently, a lot of items and all of the furniture was

left behind. After Andy’s friend moved out, a solicitor arranged the

sale of Nyth Bran. It was then sold to the Sloan

family, after they fell in love with its location.

Such a sad, sad story. I especially feel for Jane, being cut off from Whay and never seeing him again.

The one thing I still hope to find out is why Nyth Bran is in such a sorry state today.

Photo by Mark Palombella Hart (2023)

My thanks once again to Dylan Arnold for letting me have this information.