'Here we all sit, Sally my wife, Jane who is five and a half, Ann who is two and a half, and Kate who is seven (days), a mile from a hard road, with no electricity, no gas, no deliveries of anything excepting coal, provided we take at least a ton, and mail, and the post woman gets specially paid for coming here. And we are self-supporting for every kind of food excepting tea, coffee, flour, sugar and salt.'

We all know John Seymour as the godfather of a movement but it seems he stumbled upon his calling. After living on a boat John (who works as a writer) and his wife Sally (who is a potter) start looking for a house for their young family. On page 14 he states: 'Certainly we did not want a farm.' They have a hard time finding a place to live but then they are offered a double cottage in a remote location ('The Broom') for very little rent, provided they keep everything in repair. When they move in they have one daughter, a second one is born while they are living there.

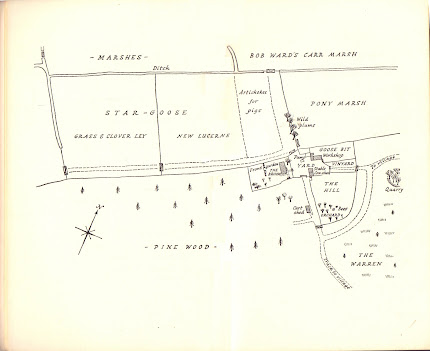

It is the remoteness that does it. 'For every single thing we wanted we had to go a mile and a half to the village to buy it. Our milk we arranged to have left every morning at some cottages a mile away from us, and every morning somebody had to go and get this.' So they get a cow (in August 1957) to provide them with milk. 'We were forced into pigs by circumstance of having three or four gallons of milk to dispose of every day.' This was when they had not yet learned how to make butter and cheese. 'And what were we going to do with all that dung? We would have to extend our gardening and farming activities. Brownie forced us, a long way, along the road that we had never planned to travel: the road to self-sufficiency and a peasant economy.'

In his biography on the Seymour family website it says: John Seymour roared through life. This is certainly the feeling you get while reading The Fat of the Land. He displays all the zeal of the newly converted, in his hurry to tell the story he often has to stop and say: but that was later, I'm getting ahead of myself.

John and Sally start growing vegetables and acquire chickens and ducks and plant fruit trees. They are novices at it all: 'We worked ridiculously hard. For not only did we have to do a great number of jobs every day - but we had to learn how to do them. (...) Whether it was planting a fruit tree, sowing some radish seed, wringing a duck's neck, gutting and skinning a rabbit: we practically had to do it with a book in one hand and the thing in the other. This made everything ten times as difficult.'

Learning to mild a cow is hard. 'I have found that there is only one real teacher for difficult things: necessity. I milked Brownie because I had to milk her'.

Though John devotes a chapter to the house (describing the rooms and what they are used for), we get no idea what it was like to live there as a family. After the first few pages the children aren't mentioned in the book.

John and Sally use books at first to find out how to run a smallholding, but a few chapters later John seems to have thrown them out. He does not care for anything"modern" and as for the poor wageslaves who live in modern houses, in villages or towns, they have lost all connection with nature and simply don't realize how badly off they are.

The book is part story, part how-to (it includes an index). John relates all their successes and failures with vegetables, their use of different kinds of wood, the slaughtering of pigs. There is also a large section on thatching and chapters on preserving, wild foods and the use of tools. John also gives an insight into the amount of money they spend and earn (John works as a writer and broadcaster, and Sally sells her pottery).

My edition from 1974 ends with an extra chapter in which John looks back on his time in Suffolk and tells us of his move to Wales. 'When we found ourselves becoming self-sufficient in food at the Broom we were probably the only family in England living this way. Now hundreds are doing it - and tens of thousands who would like to. ' The story of his Welsh farm is told in 'I'm a Stranger Here Myself' (1978).

The Broom is now available for rent as a holiday cottage.

A good source for further reading on John Seymour is his family's website Pantryfields